Property Taxes

Property taxes are a major source of funding for Oregon’s local governments. Along with Oregon income taxes, local property taxes also support public schools and community colleges. To understand how property-tax ballot measures affect taxpayers, it helps to understand some details about taxing districts, property values, levies, compression and bonds.

TAXING DISTRICTS

In Multnomah County, property owners pay taxes to the taxing districts in which a property is located. The taxing districts include a property’s school and community college districts, its city, special districts, the county and Metro. Each of these districts has its own permanent tax rate.

Assessed Values

The first of several steps in calculating property taxes is multiplying each property’s “assessed value” by the combined tax rates of all the taxing districts that serve that property. Assessed values are set at less than the real market values of most Oregon properties. In most cases, each property’s assessed value is allowed to grow by three percent (3%) per year, although the assessed value can never be more than the real market value of the property. Generally, property taxes go up three percent each year, because assessed values go up by three percent.

LEVY MEASURES

If taxing districts still need more money than they are collecting, they can ask voters to approve temporary local option levies. (The 2021 proposed renewal of the current levy for the Oregon Historical Society is an example of a local option levy.) Renewing an existing levy should not increase a property’s taxes more than the automatic three percent caused by the increase in accessed value. On the other hand, if approved, the tax rate for a new levy is added to the tax rates of other levies and of all the taxing districts that serve a property. For many properties, adding the tax rate from a new levy to the total rate will increase the property taxes somewhat. However, the amount of the increase is limited, because of a process called “compression.”

COMPRESSION

Compression keeps property taxes lower than they might be if the total tax rates could be fully applied. For example, most Portland properties have combined tax rates from all their levies and taxing districts of between $20 and $25 per $1,000 of assessed value. However, many Portland property owners pay taxes at lower rates. This is because Oregon’s Constitution sets an upper limit on property tax rates. The total taxes that any given property pays for schools are limited to $5 per $1,000 of real market value. The taxes for local government services other than schools cannot total more than $10 per $1,000 of real market value.

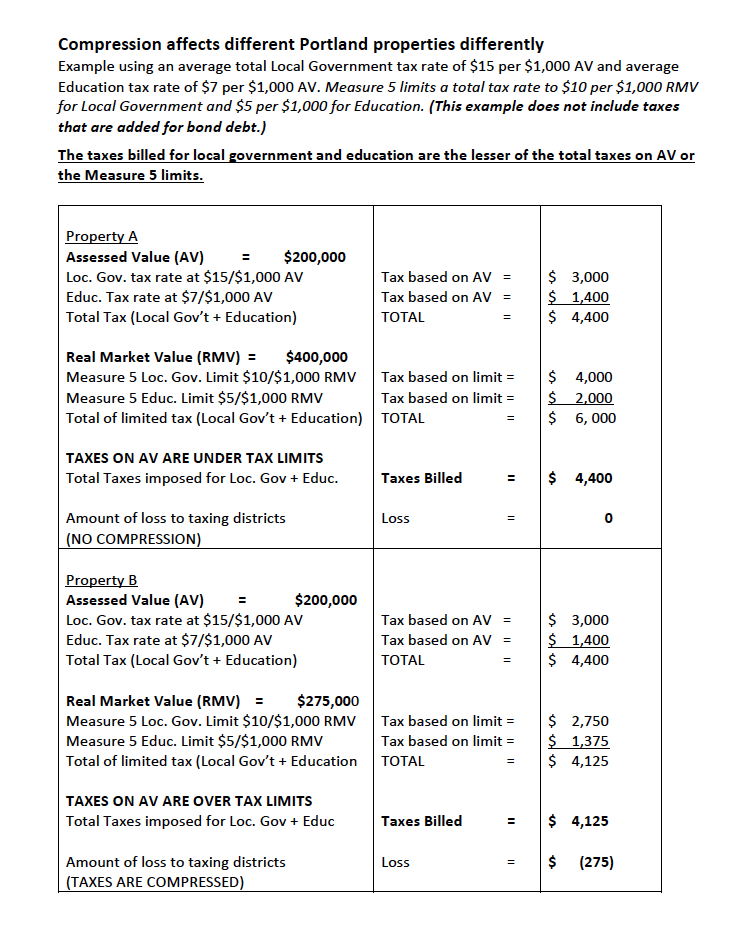

This brings us to the next step in calculating property taxes—applying the limits. Each property’s real market value is multiplied by the rate limits. The taxes imposed cannot be more than this amount. However, because the constitutional limits are based on the property’s worth on the open market, not its assessed value, the taxing district can apply higher rates to the assessed value and still stay under the rate limit that’s based on the real market value. Furthermore, two properties with the same assessed values, but different real market values, may be taxed different amounts. The closer a property’s assessed value (AV) is to its market value (RMV), the more likely the constitutional limits will “compress” the total tax rate, by limiting the taxes to $10 per $1,000 of real market value for local governments and $5 per $1,000 for education districts. The chart below shows why taxes may be different for different properties.

COMPRESSION’S EFFECT ON GOVERNMENT REVENUE

The importance of compression to taxing districts is that, even if a new levy passes, the district usually cannot collect all the taxes the levy authorizes. In addition, any losses due to the limits are shared by all the current levies in a particular taxing district. Compression reduces the revenue going to all the local option levies—those approved earlier and the new one. The reductions are applied in proportion to each levy’s share of the tax rate. On the other hand, each levy should gradually receive more revenue each year as the assessed values of the affected properties increase.

BOND MEASURES

Bonds, on the other hand, are not covered by the tax rate limits. Bonds are debts the district is allowed to incur to pay for capital improvements for buildings, roads, and equipment. If voters approve bonds, they approve collecting all the money needed for capital and interest payments on the bonds. The limits described above don’t apply. Therefore, passing bond measures does increase property taxes, unless the new bonds just replace retiring bonds.

SOME HISTORY

In the 1990’s, voters passed two constitutional property-tax limitation ballot measures that fundamentally changed our tax system. Because these property tax limitations are in the Oregon Constitution, they cannot be changed without a vote of the people.

measure 5

The first measure, Measure 5, limited growth in tax rates. Specifically, this measure placed an upper limit on the total rates that are used for calculating property taxes. All the local government taxing districts (city, the county, Metro and special districts) that together serve a particular property are limited to charging no more than a total of $10 per $1,000 of the property’s Real Market Value (RMV). All the educational districts that serve that property are limited to charging no more than $5 per $1,000 of RMV. Local option levies for additional operating expenses in these districts are included under the districts’ Measure 5 limits.

Measure 50

The second measure, Measure 50, changed how property taxes are calculated. Because of Measure 50, tax rates are now applied to a property’s Assessed Value (AV), which is usually less than its Real Market Value (RMV). (Measure 50 set Assessed Values at 10% less than their 1995-1996 Real Market Values. When new properties are added to the tax rolls, their Assessed Values also are set lower than their Real Market Values, to give them the same relative tax breaks as similar existing properties.)

In addition, Measure 50 limited the growth of Assessed Values to 3% a year. (It also required that a property’s AV can never be more than the RMV.) This means that the AV of most properties in Multnomah County will grow by 3% a year. Therefore, under most circumstances, property taxes can increase by at least 3% a year.

Measures 5 and 50 work together to keep property taxes from growing too fast. However, when voters pass bond measures or local option levies, property taxes may increase more than 3% a year.